By Dr. Joel Zarrow, Executive Director, Children’s Literacy Initiative

By Dr. Joel Zarrow, Executive Director, Children’s Literacy Initiative

I’ll just say it: I think it’s right and appropriate that the Common Core State Standards are making our nation’s educational standards more rigorous. Our kids can do it. We need it to compete. There’s plenty of room for states and localities to maintain local control over key issues such as curriculum, instruction and evaluation. And there’s great merit in expecting that children can rise to a set of standards that are consistent across our nation – not lower or higher based purely on which state they are born into. There’s no reason not to do this.

That said, and this might be heresy, all the rigmarole and debate about the Common Core is largely a distraction, regardless of where you stand on the issue. Raising the rigor of standards – what kids need to know and be able to do at a particular point in time – does not mean that teaching will get better. If students can’t read at grade level by fourth grade, and more than half cannot (NAEP, 2013), what makes us think that they will be able to, “Determine the main idea of a text and explain how it is supported by key details?” (CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.4.2). Because we say so?

The Common Core provides a bright North Star for children, but without teachers engaged in great instruction, that North Star remains a universe away. It is no small journey from the Common Core to what teachers need to do in the classroom. Teachers need to translate the broad statements of the Common Core into precise and sequenced learning objectives, often with little time or support to do so.

The Common Core provides a bright North Star for children, but without teachers engaged in great instruction, that North Star remains a universe away. It is no small journey from the Common Core to what teachers need to do in the classroom. Teachers need to translate the broad statements of the Common Core into precise and sequenced learning objectives, often with little time or support to do so.

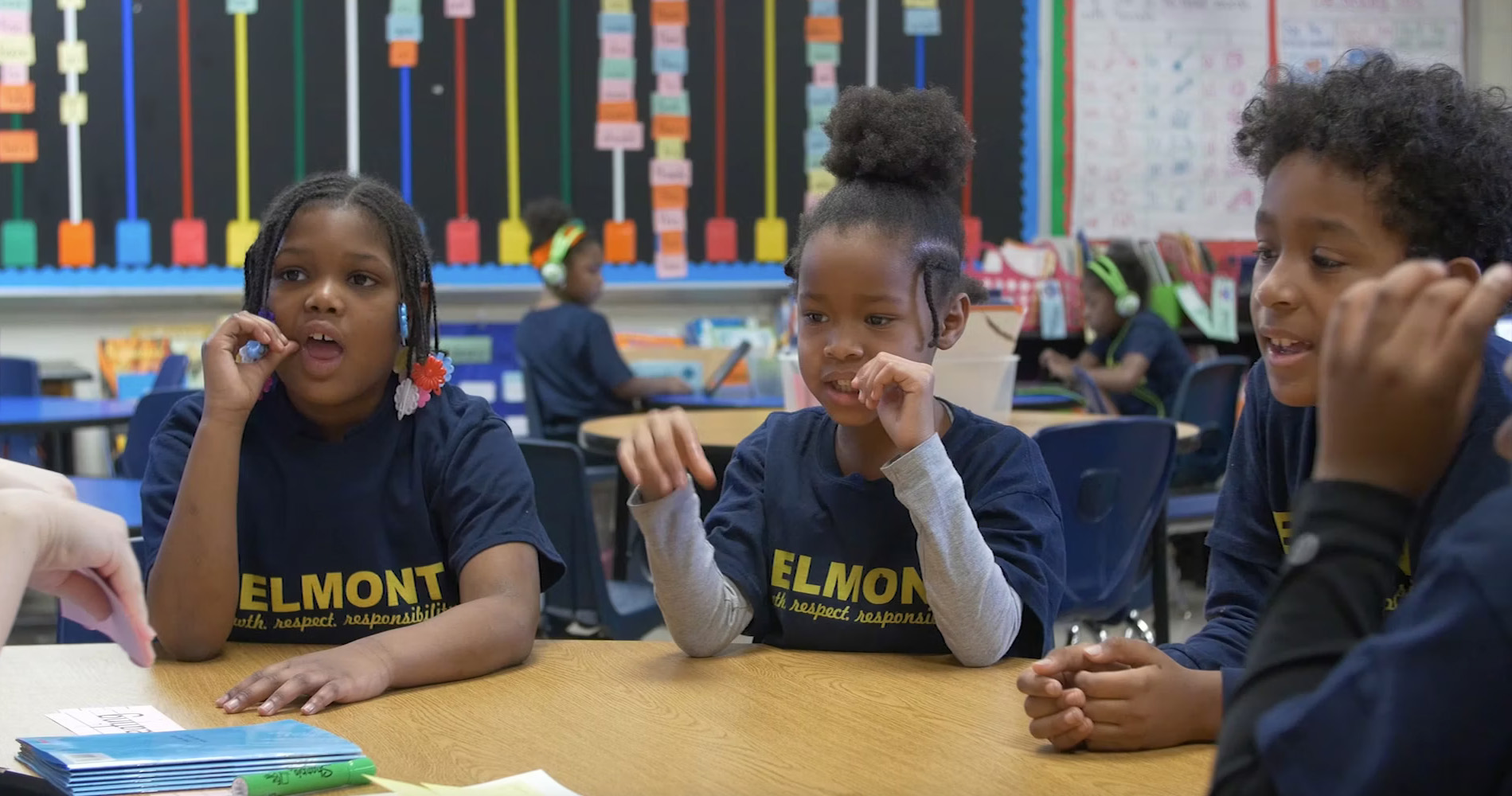

And then you’ve got the kids. The Common Core may be standardized, but kids aren’t. Teachers need to account for students with a broad range of learning needs, skills, talents, backgrounds, and preferences. With all this in mind, teachers have to plan lessons, organize materials and engage students in ways that have them connect, question, learn and grow.

Maybe it’s because having a national conversation about standards is relatively easy that people can so readily jump in to the debate. But it makes me wonder. What would happen if we focused as vigorously and boisterously on what great instruction looks like? What if we engaged in a national conversation about what support and training teachers need in order to teach like that?

What do you think? We’d love to hear from you.

Join CLI’s Breakfast Briefing to explore the future of literacy! Connect with education leaders, hear impact stories, and discover ways to get involved. Stay[..]

Empower Oregon’s educators with proven literacy strategies! Join our free virtual info session to explore research-based tools and connect with experts. Register now!

Celebrate Women's History Month with powerful stories that inspire, educate, and uplift. 📚 Download our curated guide and stay connected for more inclusive literacy[..]