English Language Learner students are often told to keep their languages separate throughout the school day—even by activity in bilingual classrooms. But students can be strategically encouraged to use their entire linguistic repertoire as they work towards the content and language goals of their lessons, especially when learning how to read and write.

“All language practices that students come into the classroom with are resources that can be used to meet the (English-centric) learning objectives we have for them,”

– Dr. Nelson Flores

Many teachers of bilingual or English as a Second Language (ESL) classrooms already permit this, but feel guilty about it, said Dr. Nelson Flores, assistant professor, of the Graduate School of Education’s Educational Linguistics Division at the University of Pennsylvania. Dr. Flores recently spoke with CLI staff and professional developers about dynamic bilingualism and translanguaging, leveraging the fluid language practices of bilingual communities to support learning in the classroom.

While much of the literature on dual language bilingual education separates students into “native-English speakers” and “native-Spanish speakers” or “native-Mandarin speakers,” Dr. Flores contends that in U.S. neighborhoods students come into classrooms with a range of bilingual competencies in both English and the language used at home, and that the goal of educators should be to develop students’ bilingual voices. He contends that educators should cultivate students’ ability to read, write and think in all of their languages and avoid forcing students to use one language completely separately from the other(s).

When he presented these ideas to teachers of bilingual or ESL classrooms, he said, “Many teachers actually felt affirmed because many of them are already engaging in what I’m calling in translanguaging but have had to do it behind closed doors because they were told not supposed to do it.”

Dr. Flores is clear: The target learning objectives don’t change, and in ESL classrooms, the target language is always English. “What’s different is what’s happening at the micro level,” he said—allowing students to use their home language(s) to more effectively learn in the classroom.

“All language practices that students come into the classroom with are resources that can be used to meet the (English-centric) learning objectives we have for them,” Dr. Flores said. “Many teachers have found that translanguaging provides a vital tool in helping their students meet those objectives.”

Allowing home languages in the classroom is “not a panacea” and will not be appropriate at all times, Dr. Flores said. When working with teachers of bilingual and English as a Second Language classrooms, Dr. Flores said he found that “After teachers’ initial response of ‘Yes, this makes perfect sense,’ then the challenge became ‘How do we do this in ways that are most effective and in ways that help our students meet the objectives we have set for them.’

“They knew that they needed to do it, but they didn’t really have support in thinking through and reflecting on how they can do this in a way that’s most effective.”

“There isn’t a recipe for it,” he said. But there are ways teachers can decide when and how to let students use their home languages.

To support students’ bilingual learning in the classroom, an educator can decide whether the lessons have a language goal that is 1) home language, 2) English or 3) bilingual and structure classroom activities accordingly. Questions Dr. Flores suggests educators consider the following when deciding translanguaging strategies:

Depending upon the answers to those questions, Dr. Flores said, a teacher could structure reading and writing activities accordingly. For example:

Dynamic bilingualism can also be employed in the classroom’s speaking and listening activities, Flores said, for example:

Consider assigning bilingual projects, translation projects and reading bilingual authors who fluidly use multiple languages in their work, he suggested.

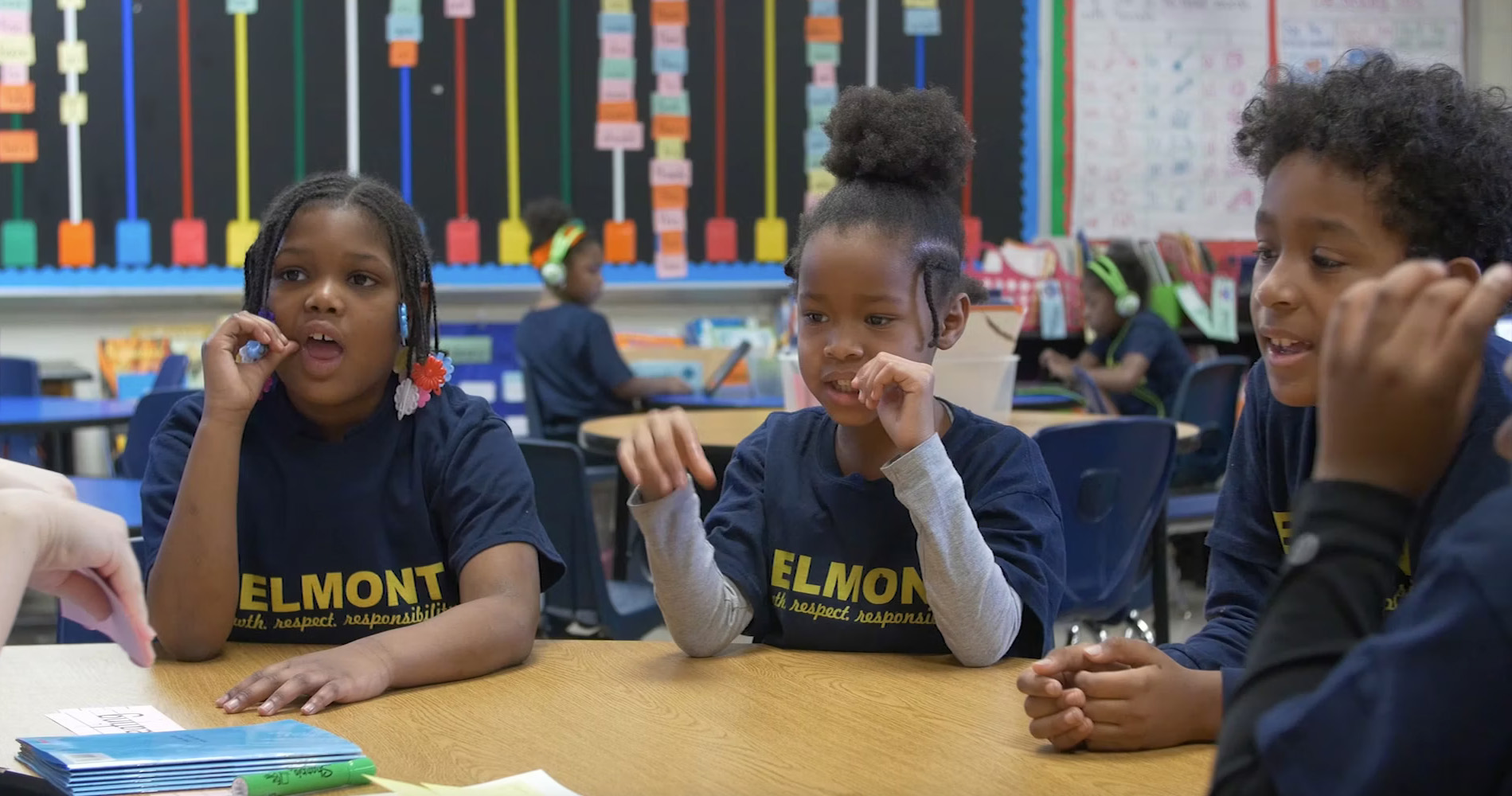

Done thoughtfully, and consciously, translanguaging helps students to become more aware of the ways that they use language already and connect their English literacy learning with language practices that they already know and use. For many students, Dr. Flores said, “it’s quite powerful to be in a classroom where their language practices – their home language and culture – are respected, valued and affirmed by the teacher.”

Dr. Flores will tour a CLI Model Classroom and, after gaining deeper insight into CLI’s work, speak again with CLI staff and professional developers about how to better support educators’ literacy instruction and students literacy learning in multilingual classrooms.

| Share this article on: |